If you work with Linux servers, containers, databases, or simply develop on a Linux machine,

your applications live on top of disks. But not all disks are the same, and understanding how

Linux handles them—from the names under /dev such as /dev/sda,

/dev/mmcblk0p1, or /dev/nvme0n1p2 to layers like LVM and RAID—can

save you from disasters and help you optimize your infrastructure.

1. Storage Architecture: Beyond /dev

The Linux kernel organizes storage into layers:

- Physical device → HDD/SSD/NVMe disk

- Block device →

/dev/sda,/dev/nvme0n1 - Partitions →

/dev/sda1,/dev/sda2 - File systems → EXT4, XFS, Btrfs

- Mount points →

/,/home,/var

Block devices vs character devices

In Linux, almost everything is a file. Hardware included.

-

Character devices

Read/written as a stream of bytes.

Examples: serial ports, some console devices, etc. -

Block devices

Accessed in data blocks (sector-based, with buffering).

Intended for storage: disks, SSDs, USB drives, SD cards, etc.

A “disk” in Linux is a special file under /dev that the kernel exposes as a block device.

Typical names under /dev

The most common block devices are named like this:

-

SATA/SCSI/USB disks:

/dev/sdX

Example: first disk/dev/sda, second/dev/sdb.

Partitions:/dev/sda1,/dev/sda2, etc. -

SD/MMC devices:

/dev/mmcblkX

Example:/dev/mmcblk0with partitions/dev/mmcblk0p1,/dev/mmcblk0p2. -

NVMe disks:

/dev/nvmeXnY

Example:/dev/nvme0n1and its partitions/dev/nvme0n1p1,/dev/nvme0n1p2.

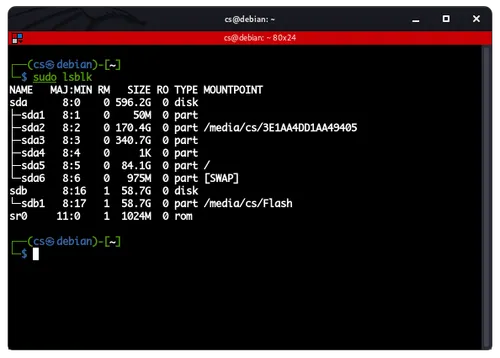

To see the relationship disk → partitions → mount points:

lsblkNAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS

sda 8:0 0 477G 0 disk

└─sda1 8:1 0 477G 0 part /

sdb 8:16 0 1.8T 0 disk

└─sdb1 8:17 0 1.8T 0 part /data

Deep inspection with system tools

According to the LPI material, these tools are essential:

# View all PCI devices (including storage controllers)

lspci | grep -i storage

# Examine connected USB devices

lsusb

# View kernel modules loaded for storage

lsmod | grep -E '(sd|nvme|usb)'Advanced diagnostic example:

# Detailed information about a specific device

lspci -s 01:00.0 -v

# Output: kernel driver in use: nvme2. /proc and /sys: File Systems That Aren’t Really Files

Linux exposes kernel information through pseudo file systems:

/sys/ - Device- and driver-specific information

# Key files for storage diagnostics

cat /proc/partitions # Recognized partitions

cat /proc/mounts # Currently mounted file systems

ls /sys/block/ # Detected block devices

ls /sys/class/block/ # Alternative viewPractical example: Check whether a disk is being detected correctly:

ls /sys/block/sd* # SATA/SCSI disks

ls /sys/block/nvme* # NVMe disks

ls /sys/block/mmcblk* # SD/MMC cardsudev, coldplug and hotplug: who actually creates /dev

The files under /dev are not “hard-coded”: they are created dynamically.

- The kernel detects a device (at boot or when hot-plugged).

- An event is generated.

- udev receives the event in user space.

- udev applies rules and creates (or removes) the corresponding entries under

/dev.

Useful concepts:

- Coldplug: detection of devices that are already connected when the system boots.

- Hotplug: detection of devices that are connected/disconnected with the system running (USB, external disks, etc.).

You can inspect how udev organizes disks with:

ls -l /dev/disk/by-id

ls -l /dev/disk/by-uuid

ls -l /dev/disk/by-labelUsing UUIDs/labels is more robust than relying on something being called /dev/sdb today and /dev/sdc tomorrow.

3. LVM: When Partitions Are Not Enough

The Logical Volume Manager (LVM) provides an abstraction layer on top of physical storage:

- Physical Volume (PV) → Physical disk or partition

- Volume Group (VG) → Pool of one or more PVs

- Logical Volume (LV) → “Virtual partition” carved out of the VG

# Typical LVM workflow

sudo pvcreate /dev/sdb1 # Create physical volume

sudo vgcreate my_vg /dev/sdb1 # Create volume group

sudo lvcreate -n my_lv -L 50G my_vg # Create 50GB logical volume

sudo mkfs.ext4 /dev/my_vg/my_lv # Format file system

sudo mount /dev/my_vg/my_lv /mnt/data # MountBenefits of LVM in production:

- Online resizing: Grow/shrink volumes without unmounting (depending on FS).

- Snapshots: Point-in-time copies for consistent backups.

- Storage aggregation: Combine multiple disks into a single pool.

# Extending a logical volume (common example)

sudo lvextend -L +10G /dev/my_vg/my_lv # Add 10GB

sudo resize2fs /dev/my_vg/my_lv # Grow file system4. MBR vs GPT: The Battle of Partitioning Schemes

| Feature | MBR | GPT |

|---|---|---|

| Max disk size | 2TB | ~9.4 ZB |

| Max partitions | 4 primary | 128 (on Linux) |

| Compatibility | Universal | Requires modern UEFI/BIOS |

Identify your current partitioning scheme:

sudo fdisk -l /dev/sda | grep "Disklabel"

# Output: Disklabel type: gpt (or dos for MBR)5. Mount Strategies for Production Systems

The LPI material emphasizes the importance of separating critical directories:

/boot→ 300–500MB (separate for recovery)/→ 20–50GB (operating system)/home→ Variable (user data)/var→ Variable (logs, application data)swap→ Depends on RAM (see LPI table)

Recommended swap size table (per LPI):

| System RAM | Recommended swap |

|---|---|

| < 2GB | 2x RAM |

| 2–8GB | Equal to RAM |

| 8–64GB | Minimum 4GB |

Mounting by /dev vs mounting by UUID/LABEL

Mounting directly via /dev/sdXN works, but it is fragile when:

- You change disk order.

- You move disks between machines.

- You add/remove devices and enumeration changes.

It is much more robust to mount by file system UUID or LABEL.

lsblk -f

# or

blkidExample of a /etc/fstab entry by UUID:

UUID=5555-6666-7777-8888 /data ext4 defaults 0 2

By LABEL:

LABEL=data_disk /data ext4 defaults 0 2

6. Advanced Cases: Beyond Basic Disks

6.1. Embedded Systems and Raspberry Pi

On ARM devices, naming changes:

# Typical Raspberry Pi

/dev/mmcblk0 # Main SD card

/dev/mmcblk0p1 # Boot partition (FAT32)

/dev/mmcblk0p2 # Root partition (EXT4)6.2. NVMe and High-Performance Disks

NVMe disks follow specific conventions:

# NVMe structure

/dev/nvme0 # First NVMe controller

/dev/nvme0n1 # First namespace of the first controller

/dev/nvme0n1p1 # First partition of the first namespace6.3. Device Mapper and Virtualization Layers

LVM, encryption and other technologies use the device mapper:

ls -la /dev/mapper/

# Common examples:

# /dev/mapper/vg0-root # LVM volume

# /dev/mapper/cryptswap # Encrypted swap

# /dev/mapper/luks-* # Disks encrypted with LUKS7. Troubleshooting: From Theory to Practice

7.1. When the System Does Not Boot

Symptom: Message “ALERT! /dev/sda3 does not exist”

Solution:

# From a live USB/CD

sudo mount /dev/sda2 /mnt # Mount real root

sudo mount /dev/sda1 /mnt/boot # Mount /boot if it is separate

sudo chroot /mnt

grub-install /dev/sda

update-grub7.2. Disks That Do Not Show Up

Step-by-step diagnosis:

# 1. Check hardware detection

dmesg | grep -i scsi

dmesg | grep -i nvme

# 2. Check kernel modules

lsmod | grep sd_mod

lsmod | grep nvme

# 3. Force rescan of buses

echo 1 > /sys/class/scsi_host/host0/scan

echo 1 > /sys/class/scsi_host/host1/scan7.3. Managing Multiple Disks in Production

# Script to uniquely identify disks

for disk in /dev/sd?; do

echo "=== $disk ==="

sudo smartctl -i $disk | grep -E "(Model|Serial|Capacity)"

done7.4. Finding and Mounting a Newly Added Disk

-

View the latest kernel messages:

dmesg | tail -n 30 -

View block devices and compare before/after:

lsblk -

Confirm the device by size/model:

sudo smartctl -i /dev/sdb -

Create a partition, format and mount:

sudo fdisk /dev/sdb # create /dev/sdb1 sudo mkfs.ext4 /dev/sdb1 sudo mkdir -p /data sudo mount /dev/sdb1 /data

7.5. Headless Server: Adding a Disk for /data

Typical scenario: a server without a graphical environment where a new data disk is added.

- Detect the new disk with

dmesgandlsblk. - Create a partition and file system as in the previous example.

- Make the mount persistent in

/etc/fstabusing a UUID:

lsblk -f # Get UUID

sudoedit /etc/fstab # Add a line like:

# UUID=xxxx-xxxx /data ext4 defaults 0 28. Professional Admin’s Toolkit

lsblk- Hierarchical view of devicesblkid- UUIDs and file system typesfdisk / gdisk- MBR/GPT partitioningparted- Advanced partitioning toolmkfs.*- File system creationmount / umount- Mounting/unmountingdmesg- Kernel messagessmartctl- Disk health informationefibootmgr- UEFI boot entry management

Professional workflow:

# 1. Identify the disk

lsblk

# 2. Check detailed information

sudo fdisk -l /dev/sdb

# 3. Create partition (GPT example)

sudo parted /dev/sdb mklabel gpt

sudo parted /dev/sdb mkpart primary ext4 1MiB 100%

# 4. Format

sudo mkfs.ext4 /dev/sdb1

# 5. Mount using UUID (best practice)

sudo blkid /dev/sdb1 # Get UUID

echo "UUID=1234-5678 /mnt/data ext4 defaults 0 2" | sudo tee -a /etc/fstab9. Hands-On Exercises Based on LPI Certification

“A system cannot boot after adding a second SATA disk. Possible cause?”

# View current boot order

efibootmgr # For UEFI systems

# Or check BIOS settings manually“Why is lspci missing on a Raspberry Pi?”

10. Conclusion: From Newbie to Storage Wizard

Mastering storage on Linux means understanding multiple layers:

- Physical layer: Disks, controllers, buses.

- Block layer:

/dev/sd*,/dev/nvme*,/dev/mmcblk*. - Partitioning layer: MBR vs GPT, partition tables.

- Abstraction layer: LVM, device mapper, RAID.

- File system layer: EXT4, XFS, Btrfs.

- Mount layer:

/etc/fstab, mount points, options.

With this knowledge you will be able to:

- Diagnose boot and mount problems.

- Design robust storage layouts.

- Manage disks in virtualized and cloud environments.

- Prepare for certifications such as LPIC-1.

- Practice with virtual machines by adding/removing disks.

- Experiment with LVM: create, extend and snapshot volumes.

- Study software RAID with mdadm.

- Explore advanced file systems like XFS and Btrfs.

And next time you see a “weird” name like /dev/mmcblk0p1 or

/dev/nvme0n1p2, it will no longer be black magic: you will know exactly what it is,

where it fits in the storage stack and how to work with it without putting your data at risk.